Reflections

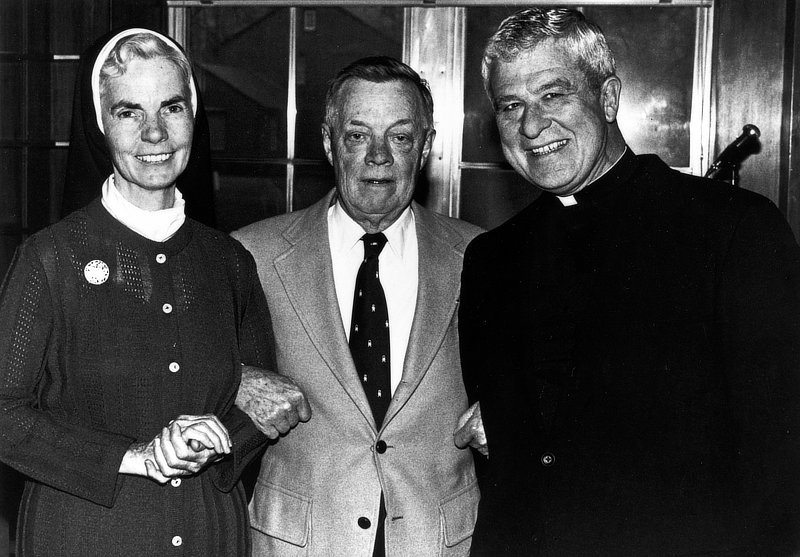

Henry Knott with Sr. Kathleen Feeley and Rev. Joseph Sellinger, SJ

Memories of my Father

These remarks were written by Martin Knott, one of Henry and Marion’s thirteen children, after the occasion of his father’s passing.

The refrain of the Communion Song, “On Wings of Eagles,” just sung by the Loyola Choir reverberates against these holy walls. I am in the pulpit of the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen. My father’s coffin sits at the communion rail. Cardinal William Keeler has just finished his eulogy and my sister Patricia is about to begin hers. Today, the throngs who have come to pay their last respects to my father, take the chill off of the mix of rain and snow and warm this cold, impersonal edifice. The solemn atmosphere is eerie as people crane their necks to hear the remarks. The view from this aerie allows me to see the entire assemblage. In attendance are the two United States Senators, three Congressmen, three retired Governors, Mayor Schmoke, Presidents past and present of Loyola, Johns Hopkins, Notre Dame, and Mount Saint Mary’s. Seated behind me on the altar are Fathers Hesburgh and Joyce from the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana and a half a dozen Bishops. In the congregation are most of the religious, business, and charitable leaders from the greater Baltimore region. The silence is deafening. The usual coughing and shuffling of feet is absent. As I scan the crowd, a sense of pride begins to fill the void in my heart created by Henry J. Knott’s passing. But I can’t help think, “Do they really know who he was, why we are having this celebration of his Catholicity, and where his life long devotion to God began?”

My father’s belief in Catholic values found its root over a hundred years go. In the late 1870’s, Mary and Martha Doyle were born to Irish immigrant patents. In 1885 their mother passed away. My great grandfather was at a loss. He couldn’t raise two young children on his own and continue to work as a carpenter. The devastating loss of his young wife and the desire to care for his precious girls left him in turmoil. This refugee from the Irish Potato Famine turned to an Irish nun whom he had befriended. She was a member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame and taught at Notre Dame College. The College also served as the Mother House for the Notre Dame Order on the East Coast. At that time, Notre Dame boarded young women attending elementary through college. The Sisters graciously housed and educated the two orphaned girls, my great aunt and grandmother, through high school. Subsequently, Mary joined the Order, graduated from the college, and eventually became Mother Philemon, the Mother Superior for the Notre Dame Order. Martha married and bore six sons. The oldest was my father Henry who never forgot the kindness of the Sisters and vowed to support Catholic education however he could. Dad’s first large gift was very personal. He donated a woman’s dormitory to the College of Notre Dame and named it Martha Doyle Hall after his mother.

I recall how my religious education started. Everyday at six a.m., Daddy would bellow, “Up and at ’em, we are leaving for church in thirty minutes.” This was a daily ritual from the time we were out of diapers to past our sixteenth birthdays. Ten minutes later he is back with more instructions, “Wash your face, brush your teeth, and say your prayers.” From another room my sister Lindsay is faking an illness. “Dad I have a headache and cramps, I can’t make it.” My brother Jimmy and I mouthed his response to each other, “Can’t means you don’t want to. Are you telling me that you don’t have anything to thank God for?” We shook our heads and were joined in laughter by a few siblings walking down the hall. Twenty minutes later Lindsay jumps into the back seat of the car while still buttoning her school uniform. No one was spared daily attendance at Mass including friends who spent the night. Daddy’s devotion to God was unwavering.

The echo of “And he will raise you up on eagle’s wings,” brings me back. I stare at the coffin and ponder, “How can the little redhead be dead?” Just seven days ago, I was standing by his hospital bed telling him jokes and asking him if he and Mother would come to our house for dinner as the doctor said that he would be released in two days. With that old glint in his eye, Dad gave a wry smile. He could not wait to get home. Dad hated hospitals. He had told me that, “Most people who go into a hospital come out in a box.” That is a strange comment coming from a man who gave Hopkins Hospital half of the land it now occupies.

Pneumonia set in the next day. It is difficult for an eighty-nine year old to recover from aneurysm surgery and near impossible when the patient contracts pneumonia. I glance back to the foot of the altar, the calla lilies that drape the mahogany casket in which Dad rests remind me of the Easter lamb, with its ever-present lilies, signifying Christ, the Lamb of God.

Our family lived on a small farm. During the spring lambing season, every morning before attending church, my brothers and I would walk the fields to see if any of our sheep were having trouble with labor. One day we espy one of our prize ewes bleating loudly and struggling to remain on her feet. Upon investigation it was clear that the lamb had not crowned. Attending to her could wait until after Mass.

When we returned home from services, I changed out of my church clothes, rushed down to the field, and gently carried the animal to the barn. The ewe had a breech. The lamb was coming out feet first and had to be turned around while still in the uterus. I was twelve and scared to death. all I could think of was, “is she going to die?” “Knucklehead, wake up and listen to me,” Daddy said. “It’s your turn to learn.” I was shocked. Was he really talking to me? Why isn’t Dad calling the vet? He always calls him when this happens.

“Martin you need to learn how to do this.”

“But I am only twelve.”

“Wash your hand with alcohol and let’s go.”

Dad helped me lay the ewe on her side. His 140 pounds strained to hold her head and front legs in order to keep the thrashing as a minimum. The smell of the alcohol stuns my nose. It masks the pleasant aroma of fresh hay and sawdust that normally permeates the barn. First, the protruding ear of the lamb had to be pushed back inside of the mother. Being extremely careful not to tear the lining, In inserted both of my hands into the uterus. It felt like warm Jell-O. Then I slowly and gently turned the lamb, so the head would come out first. When this task was just about complete, I felt something move. My body tensed. Fear engulfed me. Perspiration leaped from every pore. I stuttered, “Dad there is something moving in her.” He smiled and calmly said, “Don’t worry Martin. You’re doing fine. It’s probably a twin.” The kindness in his eyes kept me from the edge of panic. Twenty minutes later that lamb was out. Within the hour, I had delivered my first two lambs. The mother was fine and they were nursing away. It was an exhilarating feeling. I was euphoric.

We went up to the greenhouse to wash up. The two of us addressed the sink but I hesitated immediately join in this cleansing. There was something mystical about bringing life into the world and I wanted to enjoy it, if only for a brief moment. While scrubbing, my curiosity overcame my pride of accomplishment. I asked him, “Why did you have me do that? Couldn’t we have lost the ewe and the lambs?” Daddy looked at me meekly and said, “Son, God wouldn’t have let that happen. You have to understand, if you take care of God’s creature, he will take care of you.” Daddy always stressed to his children, “Keep your hands and hearts close to the land, that is where you will find God.”

The hymn resounds again, “Bear you on the breath of dawn.” Daddy was always hurrying. As a young unemployed bricklayer during the Great Depression, he had pawned Mother’s engagement ring to buy a ticket to the island of Aruba, where a friend had helped him secure a job laying bricks. Six months later, after working sixteen hour days, he returned with enough money to repurchase the ring and start his own bricklaying business.

Dad worked tirelessly. In four years he had over six hundred men working for him. The desire to achieve and support his burgeoning family never waned. By 1949, twelve of his eventual thirteen children were already born. the family’s growing needs were too much for his brick company. So Daddy branched out into the home building business to accommodate the veterans returning from World War II who were starting their families. Dad’s timing was impeccable and his success was meteoric. He quickly amassed a fortune and began his unprecedented largess.

The Hymn is there again, “Make you shine like the sun.” Patricia finishes her eulogy. She and I stand there in the pulpit for one last look at Dad’s coffin and the crowd. The pungent scent of incense hovers in the air. Cardinal Keeler approaches the bier and suddenly stops. A hush descends upon the entire congregation. For a brief moment the sun started to shine. Through one of the stained glass windows a single beam of bright light casts a beacon over the casket. It was gone in a flash. The morning air returns to a dreary mix of rain and snow. It was as if God had opened up the heavens, reached out his grateful hand, and said, “It’s time to come home, Henry.” My heart sank, I knew he was finally gone but the respect and love emanating from those gathered helps to fill the void. Resolutely I knew my father was where he always wanted to be.

Daddy always told me, “I don’t want some fancy funeral. Just put me in a pine box. The worms are going to get you anyhow.” Today, this pomp and circumstance was not wasted. We are here to pay homage, say farewell, and celebrate Daddy’s life. He had spent it teaching his children and those with whom he came into contact. Today, his unstated lesson for those of us present is, “Do not forget where you came from and never lose sight of God.”

The refrain ends, “And he will hold you in the palm of his hand.”

Remarks below are taken from a talk given by Rose Marie Porter Knott at the 20th Anniversary of the Knott Scholarship Funds

Marion Isabel Burk and Henry Joseph Knott met, courted, and were married in 1928 in Baltimore, and spent the next 67 years building a life together and, in turn, sharing the benefits of that life with their family and community.

Neither of these people had the benefit of a college education, nor did they have any money as they began their journey together. What they did have was great faith in one another, their religious beliefs, and an incredible commitment to the life they had chosen.

Their first ten years saw them through the Depression, with Henry taking any job available, including an oil rigger in Aruba, and a tomato truck driver, while Marion was getting her “Ph.D. in dollar stretching” as she managed the clothing and feeding of their six children: five girls and one boy. They were a persevering and determined young couple whose philosophy was “God Will Provide.”

With World War II on the horizon, Henry found a banker who believed in him and loaned him the money to bid on a government housing project for the war effort. No one could have predicted the benefits that would be reaped from the faith that one person had in our father. By their twentieth wedding anniversary they had added an additional three girls and three boys, moved from a row house to an eight-bedroom home, and were breathing much more easily due to their growing savings account and a flourishing business.

In the 1950’s Henry’s business expanded as he began developing property. Henry also became very active in his community, his church, and politics, and sat on numerous charitable and business boards. He raised millions of dollars for charities and always felt he could not ask others to give if he could not match them. His name became synonymous with giving.

The Knott household was, to say the least, lively. All the children attended Catholic schools. Henry and Marion worked well together in rearing their children—Henry was a strict disciplinarian and Marion was the nurturing and loving half. They both instilled a very strict and tough work ethic that taught you did not stop until the job was completed and completed correctly.

Their religious fervor was also taught. Mass was an everyday event for all school-age children, grace was said before and after all meals, the family said the rosary every night after dinner—every night—dates or no dates. The telephone was outlawed after 7 p.m.

Their philosophy on life can best be summed up in three quotes they often shared with their children:

“You are only entitled to what you work for.”

“Don’t talk about it—do it.”

“Be prepared—it was not raining when Noah built the ark.”

Marion and Henry Knott left their mark in the Baltimore area in the financial support have given the cultural, educational, medical, and scientific institutions of their community.

Henry and Marion were strong believers in Catholic education and its power to change lives. In 1980 the Marion Burk Knott Scholarship Fund was established to provide four year, full tuition scholarships to Catholic students attending Catholic elementary, secondary, and college in parts of the Archdiocese of Baltimore. In 1988, the couple established a second fund, the Marion I. and Henry J. Knott Scholarship Fund. This fund gave gifts to Stella Maris, Johns Hopkins Hospital, and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra as well as provides continued support for area Catholic hospitals, scholarships for the three Catholic universities in Maryland, and scholarships for Catholic secondary school.

These two Funds operate under the name of the “Knott Scholarship Funds” and have provided tuition support to over 1600 Catholic students since its inception.

It was the wish of the Knotts that Knott Scholars become active members in their churches, communities, and schools, taking advantage of the great gift of a Catholic education.